Last season in the NFL, 281 players sustained concussions. These numbers were reported by an independent agency outside of the NFL itself, and considered all games in the regular and preseason. This article will examine media portrayals of concussions, and how they relate to the current state of the concussion crisis in America’s favorite game. In the meantime, try watching these clips without flinching.

Concussions, CTE and the NFL

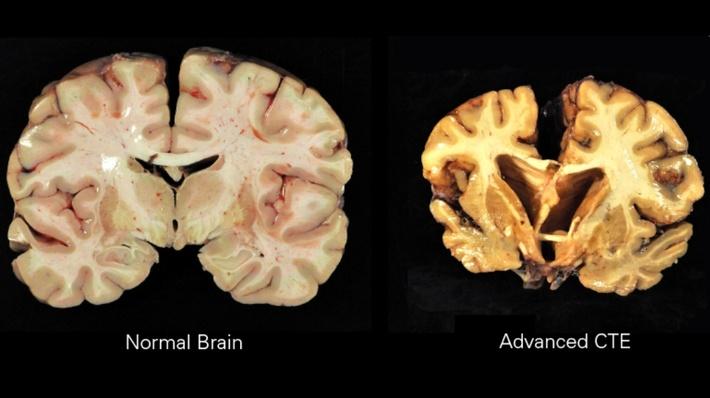

Concussions have always been a concern for players entering the professional sports industry. With football being one of the roughest sports out there, these players are at a significantly high risk for concussions. However, it is not the initial head injury that has players, activists and fans concerned, it’s a neurodegenerative disease called CTE that has been linked to repeat head trauma and known to have significantly life altering (and in some cases life ending) effects. Some of the side effects of CTE include depression, anxiety, and symptoms similar to early onset dementia.

In 2005, the brains of former Pittsburgh Steelers players Terry Long and Andre Waters were examined and it was determined that both suffered from CTE. According to CNN, both committed suicide. This was only the beginning. According to an article released by the New York Times, studies found that 110 of 111 brain scans of deceased NFL players had CTE. This included Kevin Turner, whose disease lead to the development of ALS. Former New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez was also diagnosed post-suicide with a case of CTE that experts say is the most severe they have seen yet in a person his age. For those of you who don’t follow football, Aaron Hernandez was convicted of two murders and sentenced to life in prison, where he was later found dead.

The overwhelming evidence regarding the link between concussions and CTE was not easily accepted by the NFL. Between 2005 and 2016, families of deceased players filed lawsuits against the NFL, and a notable class action lawsuit was filed and won by NFL retirees. Many players accused the lawsuit as an attempt by the NFL to minimize the severity of CTE, leading to players choosing to sue the league independently. Further, it was not until 2016 that the NFL acknowledged for the first time that concussions could be linked to degenerative brain diseases like CTE *eyeroll.* This brings up issues of agenda and power relations in the NFL. Being an executive for America’s favorite sport comes with a pretty decent paycheck, and the current concussion crisis is the biggest challenge to the NFL’s survival to date. These power struggles are common in sports, as Corrigan (2014) notes, the capitalist class articulates shared values and policy, and this is reflected in the media. A full timeline of these lawsuits can be found here.

Photo: Comparison of normal brain and brain with CTE. PC: PBS Learning Media

An occupational hazard?

Even with the Supreme Court’s approval of the 2013 lawsuit and the NFL’s admission of these ties, many players, experts and activists are still concerned with the NFL’s concussion protocol, which was recently revamped, and how strictly those protocols are being followed. Former Seahawk Richard Sherman spoke out about the protocols, calling them “an absolute joke” after doctors and coaches failed to remove quarterback Tom Savage from the field despite obvious concussion symptoms. This is not uncommon in the league. Despite advancements in head injury research, concussions are still frequently framed as everyday football injuries. Because of this, they are viewed by many as just being part of the game (Karimipour & Hall, 2017). Through this process, concussions are normalized as occupational hazards, or as just part of the game.

Photo: Tom Savage returns to game after suffering a concussion. PC: New York Times

While there is plenty of media outlining the risks of concussions and its tie to CTE such as the articles listed above, many sports fans use sources like SportsNet and ESPN to get updates on scores and injuries. According to an article by Karimipour and Hull (2017), ESPN frequently placed head injuries in articles along with knee, ligament and other more minor injuries, making them appear less significant than they actually are. Further, minimization of the severity of concussions can be found in the NFL’s 2017 season injury report. Here, the NFL does acknowledge that concussions have risen by 16%. However, this number isn’t nearly as concerning as the total number of concussions that were sustained in the NFL at 281. By leaving this number out of the article, the NFL is minimizing the impact that these numbers have on readers, and therefore minimizing the issue of concussions in the league.

These sources also tend to use players and coaches for quotes on the sustained concussion, instead of team doctors or specialists (Karimipour and Hull, 2017). This creates an issue of de-medicalization. By failing to consult health professionals and instead choosing to use athletes and coaches as “experts” on these issues, the media is taking concussions out of the medical world and placing them into the sports world. Terms like “having his bell rung” further demedicalize and normalize concussions as part of the game by failing to acknowledge the severity of concussions (Moe, 2014). The way the media discusses NFL concussions play a role in normalizing them as part of the game, and endanger the lives of players.

A Celebration of Masculinity and Violence

The normalization of concussions couldn’t occur without some very specific narratives already in place. While the way media talks about concussions themselves helps to normalize severe impacts of head injuries, the way that football itself is portrayed in the media ultimately helps to normalize violence and the issues that go along with it. Consider which player you feel to be more masculine: a kicker or a linebacker? The NFL celebrates big hits and the tough players that push their bodies to the limits every night. Aside from being celebrated, they are commodified. For example, ESPN formerly held a segment titled “Jacked Up,” which showed the biggest and baddest hits from around the league. It could be argued that many of the hits demonstrated in this segment would be considered penalties by new NFL standards. The “Jacked Up” segment, and other media portrayals of football and football players glamourize violence and therefore create an extremely masculine environment. Masculinity is a common theme throughout most professional sports, however the nature of football exaggerates traits such as aggression and violence. In fact, Messner (1992), states that a player’s masculinity is defined by how physical he is on the field. Domination over others, as well as physical superiority are important aspects of masculinity (Andersen & Kian, 2012). These are also important aspects of football itself.

So, how does this create grounds for the normalization of concussions? First; pain, injury and bodily sacrifice can be seen as admirable in this context (Anderson & Kian, 2012). This is referred to as the warrior narrative (Furness, 2016). On the other hand, withdrawal from a game or submission to injury can be seen in the opposite light. For example, Sanderson et. al (2014) notes that players can be ridiculed by coaches for refusing to play after an injury. They further state that failure to continue to compete after an injury can be viewed as the opposite of hypermasculinity: homosexuality. The need for players to assert their masculinity can lead to serious repercussions. In regards to concussions, these injuries are even more difficult for players to acknowledge because they are what Moe (2014) refers to as invisible injuries. They are not characterized by blood or gory images, and can therefore be viewed as less masculine, despite their obvious severity. The narrative of masculinity in the NFL normalizes concussions through its glorification of violence and self sacrifice, and the association between aggression and masculinity.

NFL vs. Retirees

First filed in 2013, retired NFL players sued the NFL for concussion related long term injuries. This is a long and complicated series of events, but here is a simplified breakdown: Beginning in 2009, ex-NFL players began suing the NFL for concussion related injuries. However, the league maintained that concussions could not be linked to CTE, and motioned to have the case thrown out of court. This is the first time we saw NFL players fight back against the league. In 2013, these players agreed to form a class action lawsuit against the NFL, which when eventually approved in 2015 provided five million dollars to each ex-NFL player on the prosecution (thanks CNN for your concussion crisis timeline).

However, not everyone saw this lawsuit as a victory for the players suffering with long term brain injuries. First, the NFL accepted the lawsuit without actually accepting any responsibility in the damage to the player’s brains. This was an easy way for the NFL to place themselves in the good guy role for the media without actually moving towards a safer NFL, or admitting any guilt towards the issue. While headlines like, “NFL Concussion Lawsuit Settlement Approved,” it appears as though the matter has been put to rest. It wasn’t until a year later that the NFL officially acknowledged the link between concussions and CTE. Further, in new developments to this story, the 5,000 players involved have yet to receive any sort of compensation as per the settlement. Many players and lawyers believe that the NFL is making the process deliberately difficult for players to collect payouts, and players may be lucky to receive any payment at all. In other words, the NFL may have made it through their legal troubles without a scratch, and at the same time helped to clear their name in the media.

Is the Media Changing?

While many networks such as ESPN may still be normalizing concussions, the NFL can no longer deny the link between concussions and CTE, or the growing number of concussions in the league each year. League of Denial, a documentary aired on ESPN attempted to take a stand for player safety by exposing the link between concussions and CTE (Furness, 2014). This documentary was instrumental in reframing the concussion crisis, and taking NFL head injuries out of their masculine context. For example, as noted in the Furness article, League of Denial separated former NFL player Mike Webster from the injured hero role by showing his lifeless body being examined by medical doctors (2014). It demonstrated that the players are not invincible, or warriors, but are actually just people trying to make a living. The documentary faced severe pressure from NFL commissioner Roger Goodell (Furness, 2014), who did not want it to air, but carried on regardless. Further, Anderson and Kian (2012) studied media relating to quarterback Aaron Rodgers withdrawing himself from a game after sustaining a head injury. They found that journalists appeared to value health over the warrior narrative discussed above. This challenges the notion of hegemonic masculinity that was previously noted, and may demonstrate a shift in the mainstream media’s attitude towards concussions.

References

Anderson, E., & Kian, E. (2012). Examining Media Contestation of Masculinity and Head Trauma in the National Football League. Men and Masculinities, 15(2), 152-173.

Corrigan, T. F. (2014). The Political Economy of Sports and New Media. In A.C. Billings & M. Hardin (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media (pp.43-54). New York: Routledge.

Furness, Z. (2016). Reframing concussions, masculinity, and NFL mythology in League of Denial. Popular Communication, 14(1), 49-57.

Karimipour, N., & Hull, K. (2017). Minimized, Not Medicalized: Media Framing of Concussions in the NFL on ESPN.com. Journal of Sports Media, 12(2), 45-77.

Messner, M. (1992). Power at play : Sports and the problem of masculinity / Michael A. Messner. (Men and masculinity).

Moe, A. (2014). Banging heads- Media portrayals of injuries in professional football before and after the death of Mike Webster.

Rodgers, K. (2014). “I Was a Gladiator”:: Pain, Injury, and Masculinity in the NFL. In The NFL: Critical and Cultural Perspectives (p. 142). PHILADELPHIA: Temple University Press.

Sanderson, J., Weathers, M., Grevious, A., Tehan, M., & Warren, S. (2016). A Hero or Sissy? Exploring Media Framing of NFL Quarterbacks Injury Decisions. Communication & Sport, 4(1), 3-22.